The uncertainty of getting (and keeping) a student visa in the age of Trump.

Zijing Tan, a Weinberg third-year, entered the United States this summer for the fifth time — but this time, Tan was particularly nervous about coming back.

Immediately after getting off a 15-hour international flight, Tan found herself in a U.S. Customs line that she couldn’t see the end of at Chicago O’Hare International Airport. She waited impatiently as permanent residents and U.S. citizens passed quickly in the other lane. Many other students around her found themselves in even more dire situations, stuck in long lines while their connecting flights took off.

Moving up the line bit by bit, Tan could finally see the immigration officers. She had heard rumors of deportation and was even more apprehensive this time.

“I have seen people being led away to a separate room right before me. All I can think of is whether I need to switch a line and avoid this officer who has sent all four people before me for more questioning,” Tan says. “It is quite scary to see people being denied entrance or even returned back to their home country.”

International students who are neither U.S. citizens nor permanent residents of the United States need to obtain an F-1 visa in order to study in U.S. schools. They must collect documents like their college acceptance letter, tuition invoice and letters from the university international office and submit them with an online application to U.S. consulates in their home countries. Students who are older than 14 are required to schedule an interview with U.S. immigration officers at the consulate or embassy.

Usually, processing an F-1 visa application takes about two weeks to a month, but some international students have reported a much longer processing time after new changes enacted by the Trump administration. According to Theresa Johnson, the interim director of the Office of International Students and Scholar Services, a prolonged processing time is one of the significant changes in the recent administration.

“In this past summer, lots of our students and visitors from China reported having to wait longer to obtain their visas,” Johnson says. “Rather than waiting for a couple weeks after handing in their application materials, some of them had to wait for a couple of months.”

Changes in the Trump administration

According to the U.S. State Department website, obtaining an F-1 visa does not necessarily guarantee entry into the United States. Rather, it only allows international students to board a plane to travel to the United States and request permission at customs, while a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officer will decide whether to allow access on a case-by-case basis.

On August 23, Harvard freshman Ismail Ajjawi, a Palestinian student, was denied admission to the United States even though his visa application and materials were pre-approved. CBP declined to comment on the specifics of this case but claimed Ajjawi was denied entry “based on information discovered during the CBP inspection.”

Ajjawi told The New York Times that CBP officials searched his phone and laptop at Boston Logan International Airport. He says that the CBP officer yelled at him in the airport because people in his friends list posted anti-American content on their social media accounts.

A Northwestern student from Iran was turned away trying to board a flight to Illinois before this fall quarter. The Office of International Students and Scholar Services declined to disclose personal information about the student as the case is still pending. Johnson says that she doesn’t know why his visa was revoked, but the University has hired an attorney and filed another visa application which is currently pending, according to University Spokesperson Bob Rowley.

Even before the Trump administration, obtaining a student visa was often a burden. According to Tan, while having one’s visa denied seemed a distant possibility, the fear has always loomed above international students’ heads.

“Application to U.S. colleges doesn’t really end with the acceptance letter,” Tan says. “You still need to obtain a visa, and it does take time.”

On July 13, 2018, a policy memorandum by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security gave U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) officers more power in the process of visa applications. According to the policy memorandum, officers no longer need to ask for additional information from the applicants to justify their decisions. The Trump administration also announced potential visa time limits, but these have not yet been enforced. Beijing native and Medill third-year Yahan Chen is concerned about this increased antagonism toward international students, and Chinese students specifically.

“The new policies during the Trump administration are possibly a sign of the increasingly hostile attitudes toward international students,” Chen says. “We think that it might also continue into the next administration.”

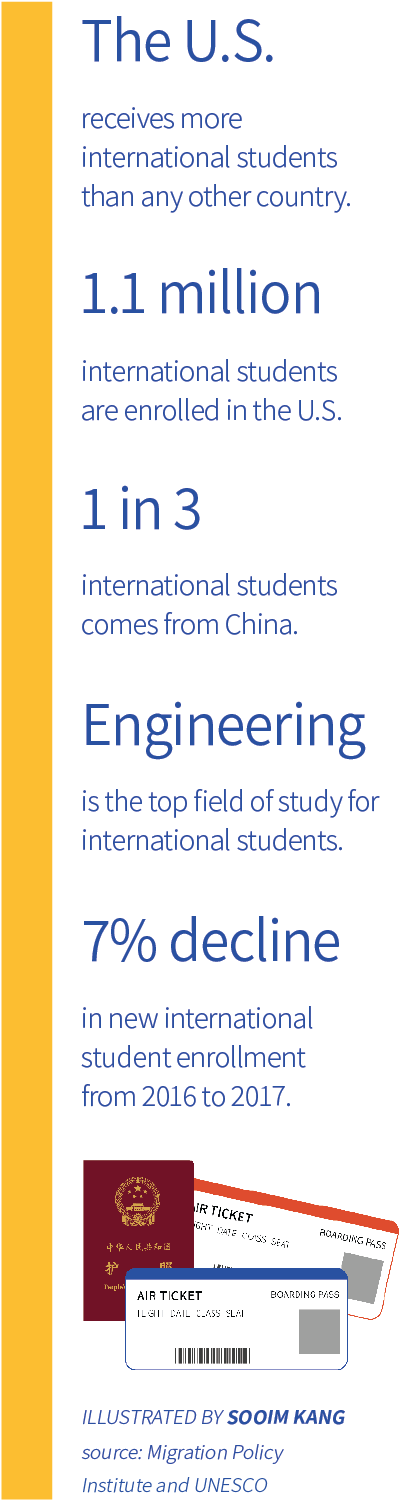

In a State Department report issued in 2017, the number of F-1 visas was down 17 percent from the last fiscal year, almost 40 percent below the peak in 2015. According to Caixin Global, a Chinese financial newspaper, the increasingly strict application process for student visas deterred many Chinese international students from coming to U.S. colleges. According to the Open Doors Report released by the Institute of International Education this year, the rate of increase of the Chinese international student body in the U.S. this academic year has nearly halved from last year. Overall, international student population growth in the U.S. has dropped to only 0.05 percent.

Tan says even students who have spent time studying in U.S. colleges were denied entrance this past summer, based on what her parents told her and what she saw on the news.

“It gets you thinking about whether you will be the next one,” Tan says.

In the summer of 2019, nine Chinese international students were denied admission to the U.S. at Los Angeles International Airport. Customs and Border Protection officials detained the students, who were headed to Arizona State University, and sent them back to China. News like this made international students’ parents, including Chen’s mother Huaying Sun, more alarmed.

“Parents around me were all talking about the potential impacts of the new policies when they first came out,” Sun says. “I didn’t know what it might mean for Yahan, but I know that she might have a harder time in the United States.”

Sun urged her daughter to refrain from posting any controversial viewpoints on social media after hearing about students like Ajjawi being sent back to home countries because of their social media.

“There is very little that a parent can do as we are rather far away from our children and know little about the whole complicated process. All we can do is to tell them to be more cautious,” Sun says.

Johnson says that these concerns are valid, as USCIS has started to ask some students to report their social media activity and other private information during the application process and at customs.

This past June, Northwestern Provost Jonathan Holloway and the Office of International Students & Scholar Services sent an email to the Chinese student body about the recent policy changes addressing the increasing concerns in the community. Writing in both English and Mandarin, the school administration said that no Chinese students at Northwestern have run into problems so far. Johnson says Northwestern’s administration considers every international student to be crucial to the community and will do everything they can to ensure their stay in the University.

“We really value the contribution by international students on Northwestern’s campus,” Johnson says. “Many people across campus want to support the international student body in such times.”

Postgraduate problems

Obtaining a student visa might not have been as concerning to international students prior to the Trump administration, but securing the chance to continue working in the United States after graduation has always been on their minds.

Medill third-year Nina Cong, who also majors in computer science, says that more and more companies choose not to sponsor international students to get a non-immigration work visa, also known as an H-1B visa.

McCormick fourth-year Jenny Kim’s experience mirrors Cong’s. According to Kim, her status as an international student puts her at a disadvantage when searching for internships and jobs.

“Even if I share the same experience and qualifications with my peers, it is still much harder for me to secure a job,” Kim says. “Sometimes when employers hear that I am an international student, they just shut the whole conversation down.”

Even if the company agrees to sponsor students, obtaining an H-1B visa is still a challenge. Applicants need to go through a strict screening process and enter into a lottery system to determine who gets a legitimate visa for working in the United States. According to an analysis of USCIS data by the National Foundation for American Policy, denial rates for new H-1B visa petitions for initial employment increased five times over from 6 percent in 2015 to 32 percent in 2019.

Besides securing a visa for work, the F-1 student visa also comes with an Optional Practical Training (OPT). Students are eligible to apply for up to 12 months of OPT employment authorization before and after completing their studies as long as they are engaged in work directly related to their field of study. Many international students count on the OPT period to obtain their permanent visas. According to the USCIS website, if a student is majoring in a STEM field, they can apply for a 24-month extension period, giving them more time and opportunities than other students. Some international students factor OPT extension into their consideration for majors.

“The OPT period is crucial for some of us who need that additional time to figure out whether we want to stay in the United States for work and, more importantly, whether that’s possible,” Chen says. “When Northwestern decided to incorporate economics in STEM, I was really glad as I can have the additional time to figure everything out.”

Like Chen, Cong also considered these benefits when she first chose computer science as her second major.

“I didn’t solely choose my major because of the OPT benefits that come with it,” Cong says. “Nevertheless, it was definitely on my mind when I decided to major in computer science.”

However, Kim says that the extension of OPT is nice in theory, but it doesn’t transfer to employers’ attitudes in reality. The long-term uncertainty of international students’ visa status still makes employers hesitant to hire them.

“Companies don’t want to bother with sponsoring you because they don’t see themselves employing you after you graduate,” Kim says. “It puts international students at a disadvantaged position as companies want to hire interns who can work for them in the future. But the visa status of international students might make that unlikely.”

Johnson says the odds for obtaining a work sponsorship after graduation are not good, especially if students want to work for a for-profit company. She suggests international students also look at non-profit organizations and universities because they are more likely to sponsor international students.

“As a higher-education institution, Northwestern can file H-1B application at any time in the year with an unlimited number. It is true that they are more likely to get less salary, but non-profit organizations and universities might be good places to start their careers,” Johnson says.

For Tan, studying and working in the United States has always been what she wants. Her original plan for the future doesn’t seem so definite now, as strict policies target international students like her.

“I initially had a clear plan for myself that I would finish my undergraduate studies at Northwestern, then pursue a Ph.D. degree in the U.S. and find a job in some U.S. companies,” Tan says. “As more of these policies started to come out, I don’t know if I can or even want to stay here any more. It is sad to realize that you might not even be welcomed.”