I must look a little strange biking north on Ridge Avenue right now. Scores of students wearing purple sweaters are walking back to campus from Ryan Field and some of them shoot me a look as if to say, “Where are you going? The game is about to end.”

I keep my head down and continue peddling, putting in more effort as the incline steepens. Turning left on Isabella St., I can see a stretch of golf course begin to materialize just beyond a small bridge.

I’m not here to play golf, and I’m not going to the football game, either. I’m visiting a phone booth along the eleventh hole that will allow me to speak with the dead.

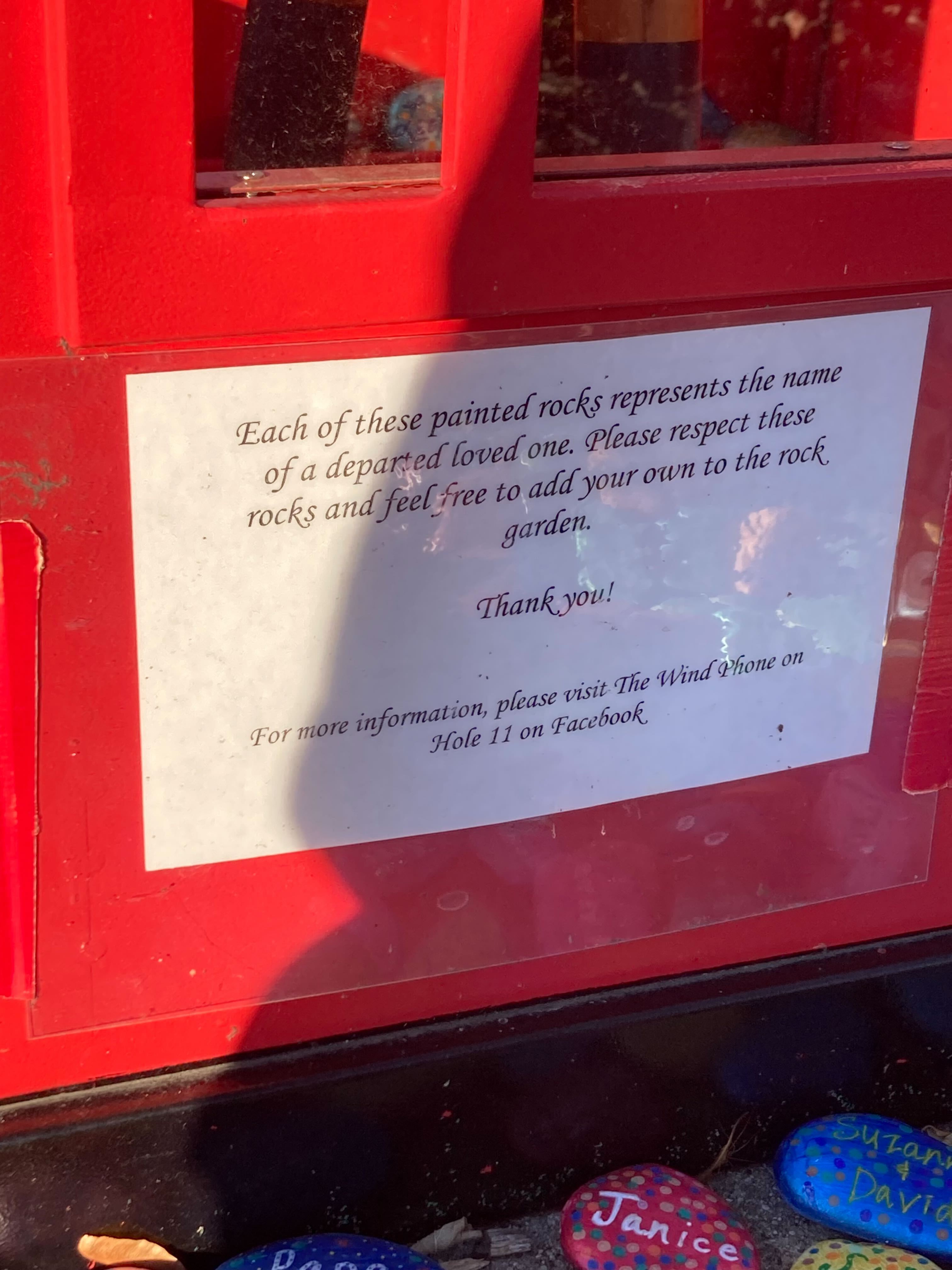

A red London-style phone booth stands alone between the North Shore Channel and the green expanse of the course. Sunlight pierces its horizontally segmented windows. Colorful rocks lie at its base, each of them bearing a different name. I park my bike, I look around to see if anyone is watching me and I go inside. There’s a sign on the wall that reads, “Welcome. This phone is for everyone who has lost a loved one.”

The first wind phone was invented in 2010 by a Japanese architect named Itaru Sasaki, whose cousin had recently died of cancer. Looking for a way to process his grief, Sasaki bought a used pay phone and placed it in his garden. The pay phone was untethered to an electrical system and unable to make calls, but Sasaki would sit there and speak with his dead cousin.

“Because my thoughts couldn’t be relayed over a regular phone line, I wanted them to be carried on the wind,” he said in an interview with Japanese TV channel NHK Sendai.

After Japan was rocked by a deadly tsunami in 2011, wind phones popped up around the country as newly bereaved people sought ways to process a national tragedy. In years since, wind phones have occasionally popped up in other parts of the world: Clarksville, Tennessee; Haliburton, Ontario; Silverton, Colorado; Kihei, Hawaii; Savigné L’Evêque, France.

A wind phone usually meets two basic requirements. First, it must be unable to make phone calls. Second, it must be situated in a semi-private and natural setting. Evanston’s wind phone checks both boxes. It sits on Canal Shores, an 82-acre publicly accessible green space and golf course flanked by the Chicago River’s North Shore Channel.

While many residents have used the Canal Shores wind phone to mourn their loved ones, the booth was originally installed to honor Oliver Leopold, a 19-year-old graduate of Evanston Township High School who died unexpectedly in December 2021.

Even before his death, Oliver was well-known in Evanston, initially as a wunderkind entrepreneur and later for his contributions to the city’s emergency response infrastructure. At 10 years old, he was profiled by the Wall Street Journal for his precocious investment portfolio. In middle school, he was invited to speak at a Northwestern University entrepreneurship event.

In high school, Oliver participated in Evanston’s Fire Explorer Program, an initiative aimed at teaching the basic skills of firefighting and emergency medical services to teenagers. During his time in the program, he created an emergency response app that was quickly adopted for use by Evanston’s Fire Department. He was eventually elected to the Evanston Fire Association, becoming its youngest member.

Seeking to make a difference during the COVID-19 pandemic, Oliver graduated early from high school to work as an emergency medical technician while pursuing his paramedic degree. He worked at Evanston’s North Shore hospital, performing intubations and learning how to deliver babies.

Oliver also had a YouTube channel with more than 11,500 subscribers where he made videos with titles like, “3D printing my voice to see if it dropped,” “How to Get a Debit Card as a KID/TEENAGER” and “TOUCH AND GO (Oliver Flies a Plane)”.

In the third video, a 15-year-old Oliver takes off and lands in a small airplane. For most of the video, only the back of his head is visible. Toward the end, Oliver turns his head slightly to gaze at the world hundreds of feet below. It’s shocking to see a face that young peering over an airplane cockpit. It’s even more shocking that his face bears the look of a seasoned veteran.

“Oliver was the type of person who could go into any line of work and be successful,” said Megan Kamarchevakul, Field Chief of Emergency Medical Services for Evanston’s Fire Department. “It’s clear his legacy and service to the community continues to live on through the wind phone.”

For those who knew Oliver, the wind phone is a fitting testament to everything he represents. It’s inventive, it’s bold, and perhaps most importantly, it helps people who are in pain. It functions not as a static signpost but as a living mechanism with a purpose.

“The wind phone is so who he was,” said Mary Leopold, Oliver’s mother.

After Oliver’s death, Mary read about Sasaki’s invention and saw an opportunity to build something out of her grief. With the help of family friend Pat Hughes and the owners of the Evanston-based Secret Treasures Antiques, she raised enough money to purchase and transport the replica vintage phone booth from a seller in Texas.

Pat Hughes contacted Matthew Rooney, the president of Canal Shores, about allocating space for the wind phone along a walking trail. The idea resonated with Rooney, whose wife had recently died after battling dementia.

Rooney installed the phone booth with a team of three women, including Mary Leopold. Two of the women had recently lost a son and one had lost a husband.

“In some ways, it’s individual mourning and in some ways it’s communal,” said Rooney. “I go by there and sit by myself and think about my wife. Then I see Oliver’s name there and I think about that.”

Since its installation, a team of volunteers from Canal Shores has worked to keep the wind phone in good condition and added lights so it remains visible at night.

Mary said the phone booth has been a source of comfort for her family. She and her husband often walk there and sit on a nearby bench. In December, she held a candlelight vigil for Oliver there.

Mary only once used the booth’s rotary phone to speak with Oliver and described the experience as profoundly affecting.

“It seems like it would feel kind of kooky but it just doesn’t,” she said.

Although the wind phone is a vital resource for Oliver’s friends and family, Mary has always wanted it to be accessible to everyone.

“What I find absolutely incredible is the ability of Mary to still think of and be able to serve others, even while she and her family are grieving,” said Kamarchevakul.

Over the past two years, Evanston residents have embraced the wind phone with open arms and used it as an accessible grieving device.

“It’s catching on, a lot of people are learning about it,” Mary said. “People have reached out to me and said how much it means to them to have this space.”

On two sides, the booth is bound by dozens of colorfully painted stones. “Each of these painted rocks represents the name of a departed loved one,” reads a sign just above.

“I hope it’s a symbol of how we can grieve as a community,” Mary said. “In American culture, there is so little ritual surrounding death. People don’t want to talk about their grief because it’s really hard.”

Evanston’s wind phone is a rarity: there are cemeteries tucked behind gates and hidden from view; synagogues, mosques, temples and churches where religious ceremonies take place to honor the dead; parks, canyons, lakes and beaches – beautiful outdoor areas that allow for moments of quiet contemplation. But non-denominational public spaces designed for the expressed purpose of mourning are few and far between.

Rooney came to understand this firsthand one day after playing golf. As he was leaving Canal Shores, a woman approached him asking for directions to the wind phone. She wasn’t from the North Shore and had driven a considerable distance to Evanston after getting off of work.

“Her husband had died a few days ago from a heart attack, and she wanted to sit in the wind phone to say goodbye,” Rooney said.

In 2021, a novel called The Phone Booth at the Edge of the World was published. The novel revolves around a man and woman who independently travel to grieve at a wind phone in the wake of Japan’s 2011 tsunami. Perhaps predictably, they cross paths and fall in love.

I haven’t yet read the novel, but sitting in the booth at Canal Shores, I find myself thinking about its claim: our capacity to grieve is intertwined with our capacity to love. I look at the arrangement of colorful stones outside the window and the framed photographs inches away from my face.

I think about the community of people who built this place, who maintain it and who continue to visit it. I realize that just by sitting here, I have somehow become part of that community. I unhook the phone and feel the weight of it in my hand.