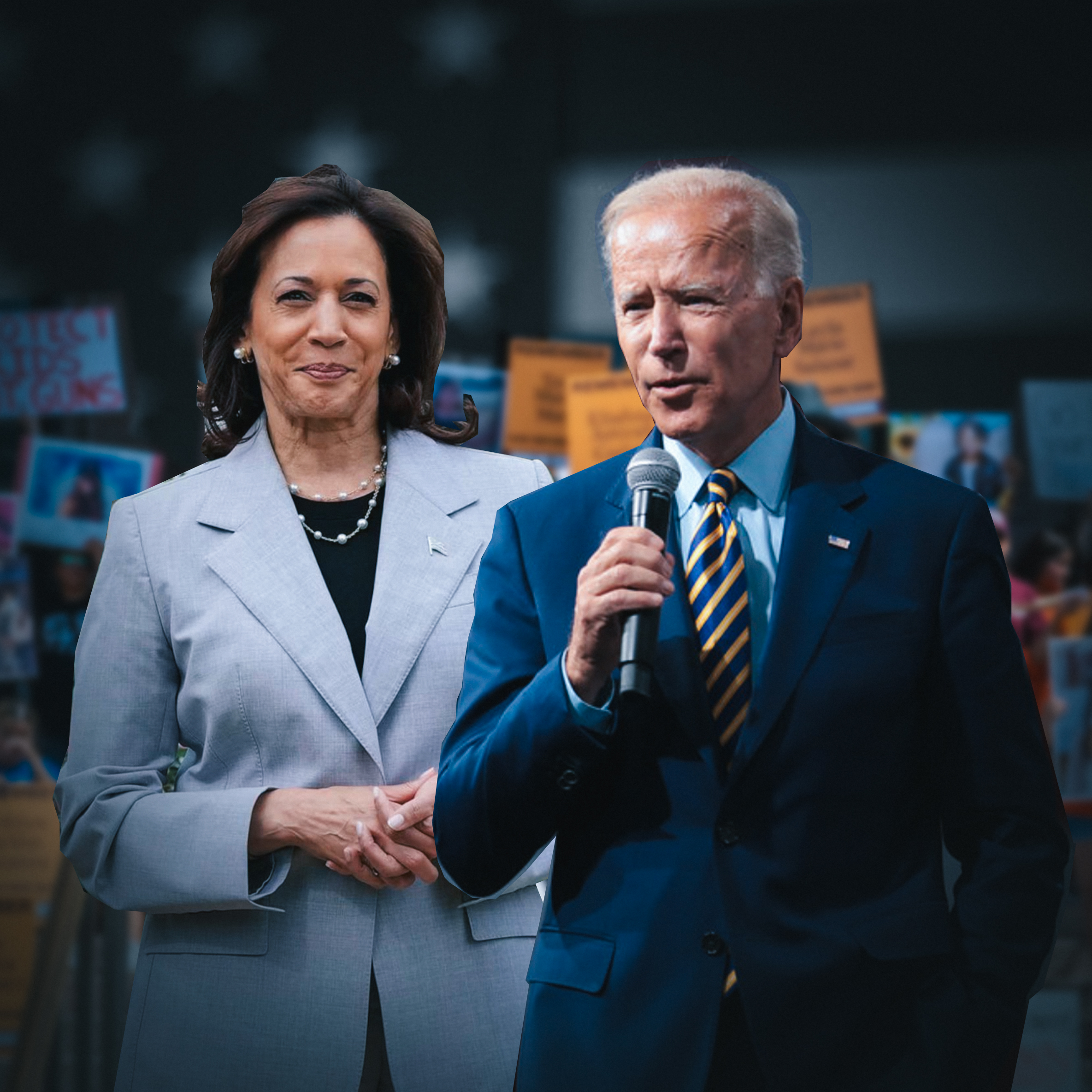

President Joe Biden announced the creation of a federal Office of Gun Violence Prevention on Sept. 22. The Office, which is overseen by Vice President Kamala Harris, hopes to coordinate government responses towards an epidemic of gun violence. The U.S. has already seen over 30,000 deaths this year, and over 54 shootings on college and K-12 campuses.

“We all want our kids to have the freedom to learn how to read and write in school instead of duck and cover, for God’s sake,” Biden said at the Rose Garden announcement.

The new Office has the potential to shape the federal government’s responses to gun violence and represent a watershed moment in gun violence prevention. Or, it could do none of that.

Understanding which result the future will bring requires a bit more detail, a fair amount of history and a lot more federal policy.

What is the Office of Gun Violence Prevention?

Though Biden has a policy record that gun violence groups generally criticize, the creation of a federal office tasked solely with the prevention of gun violence demonstrates the White House’s renewed commitment to the issue.

Because thoughts and prayers are not enough.

— President Biden (@POTUS) September 22, 2023

@VP and I just created the first White House Office of Gun Violence Prevention.

“I think the creation of the Office indicates that the current Administration knows that this trajectory cannot continue,” Mirabella Johnson, Weinberg fourth-year and co-founder of Northwestern’s Students Demand Action chapter, said over email.

The Office aims to tackle gun violence with four specific approaches, as outlined by its inaugural incoming director Stefanie Feldman in the Sept. 22 announcement.

Chief among the Office’s responsibilities is coordinating federal efforts with states, ensuring that the billions allocated to communities and schools are used as intended. The Office also intends to establish mental and physical counseling for survivors of gun violence, as well as research further executive actions.

The most ambitious goal is implementing community violence intervention (CVI), local programs which attempt to reach groups at risk of engaging with gun violence and connect them with a variety of resources. It’s an approach that advocates say is particularly effective. In late 2022, the Department of Justice awarded $100 million in funding to CVI programs across the county, resulting in the growth of such programs.

“The idea continues to be – always has been at its center – is that individuals that are strong, that experience disproportionate amounts of violence,” said Andrew Papachristos, Professor of Sociology and Faculty Fellow at Northwestern's Institute for Policy Research. “[They] know the most about what's happening on the ground, and can often hence provide its most basic solutions to dealing with conflicts.”

Papachristos is the faculty director of CORNERS: The Center for Neighborhood Engaged Research and Science, a Chicago group focused on “improving health and safety for more equitable neighborhoods.” As shown by Papachristos’s own research, CVI can help fill in gaps and even replace traditional violence prevention.

But it comes with risks – especially to those putting in the work themselves.

“Many of the people who are working in this community violence intervention work have lived in these neighborhoods with high rates of violence, have maybe been incarcerated themselves,” said Judith Moskowitz, a professor of Medical Social Sciences at the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. Moskowitz currently leads a team investigating burnout prevention among Chicago’s front-line intervention workers.

“Then they come to work,” Moskowitz continued. “They're being re-exposed, continuously exposed to the trauma of gun violence. It takes an additional toll.”

Solutions – whether via CVI or otherwise – will require efforts from multiple fields, from healthcare to legal reform.

“This is not just about fixing one-third of the problems,” said Nanzi Zheng, a Northwestern Doctoral Student researching links between juvenile detention and gun violence. “We need to build safer communities, so that people don't feel the need to own guns or carry guns.”

Activists were also pleased with the inclusion of two prominent gun violence prevention leaders as deputy co-directors of the Office. To advocacy groups who have long pushed for the creation of such an office, it signifies that the White House not only wants to listen to their demands but also integrate the people who pushed for them.

“All fellow activists I have encountered care deeply about gun violence prevention work for the benefit of everyone,” Johnson said. “In my opinion, this – gun violence – should have never been a politicized matter. This is a public health crisis, and we need to look out for one another.”

What has the Biden Administration done previously to combat gun violence?

Going into the 2020 election, Biden made gun violence a key issue of his platform. The past ten years had seen an exponential rise in gun-related violence, and dissatisfaction with current firearm laws only continued to grow.

It’s long past time we take action to end the scourge of gun violence in America.

— Joe Biden (@JoeBiden) November 1, 2020

As president, I’ll ban assault weapons and high-capacity magazines, implement universal background checks, and enact other common-sense reforms to end our gun violence epidemic.

Biden’s promises, while not as sweeping as other candidates, still represented a monumental change in U.S. gun laws. Gun control groups endorsed the candidate's plans, and activists reacted to his victory with cautious optimism.

In his first two years, Biden took some executive actions, but chaos in congress prevented major legislation. During this period, gun violence in America reached an all-time peak – gun homicides rose 45% from 2019 to 2021. Guns Down America, a gun reform group, gave Biden a “D+” for his efforts, and multiple organizations rallied outside the White House to demand more comprehensive plans.

Some progress came in June of 2022. Biden signed the Bipartisan Gun Safety Bill into law in the wake of mass shootings at a Uvalde, Texas elementary school and Buffalo, N.Y. supermarket. The bill, which represented the most significant gun legislation in over three decades, finally implemented some of Biden’s campaign promises, expanding background checks and providing over $13 billion in funding for school mental health resources.

A year later, the bill has largely been a success. Politicians and activists alike praised the passage, and major gun violence prevention groups came together to endorse Biden for 2024.

These endorsements, however, were more jaded than in 2020. While Biden had managed to sign a historic piece of legislation into law, it had only passed due to recent gun violence. With Congress locked into stalemate once again, activists weren’t excited about Biden. They simply had no other choice.

In April, Biden said, “I have gone the full extent of my executive authority to do, on my own, anything about guns…I can’t do anything except plead with the Congress to act reasonably.”

Read about the other ways the Biden-Harris administration can take executive action to fight gun violence ⬇️ https://t.co/2S8BI73trX

— Everytown (@Everytown) January 29, 2021

What does the future hold for the Office?

The Office still faces significant constraints. Any major gun control changes are likely to require passage through Congress, which remains deadlocked on the issue. And without cooperation from Congress, many of Biden’s main promises – including the ban of high-powered magazines – remain out of reach. But Biden’s actions are as much a practical step forward as they are a preview of 2024.

“If members of the Congress refuse to act, then we’ll need to elect new members of Congress that will act,” Biden remarked on September 22. "The safety of our kids from gun violence is on the ballot.”

The electoral landscape certainly has shifted from 2020. A majority of Americans now say that gun violence is a major problem, and that they would like stronger legislation. This position is especially popular among young democrats, a voting group still skeptical about the prospect of Biden’s second term. Present at Biden’s announcement was Rep. Maxwell Frost (FL-D), a gun violence survivor and the first member of congress from Gen Z – a demographic that will become increasingly relevant in 2024.

While it’s impossible to predict how effective the Office of Gun Violence Prevention will be, gun control activists see it as a definitive step in the right direction and a sign of encouragement to keep fighting.

“This is building one piece that has been absent,” Papachristos said. “It's a vital piece. It's a big piece. And so it gives me hope.”

Thumbnail designed by Kim Jao / North by Northwestern