The 2000s and 2010s saw a trend of Oscar-nominated movies about the Holocaust that Maus author Art Spiegelman dubbed “Holo-kitsch.” The sudden surplus of these narratives in popular culture can have the adverse effect of glorifying, romanticizing and even potentially downplaying one of the most horrifying chapters of human history.

While this media pattern has lessened in recent years, it has left me with a heightened sense of skepticism towards new Holocaust movies. Despite this, I was cautiously excited when I first heard about Jonathan Glazer’s Zone of Interest. After seeing it in theaters, I was left to contemplate it almost nonstop for days. It was unlike any Holocaust movie I’d ever seen.

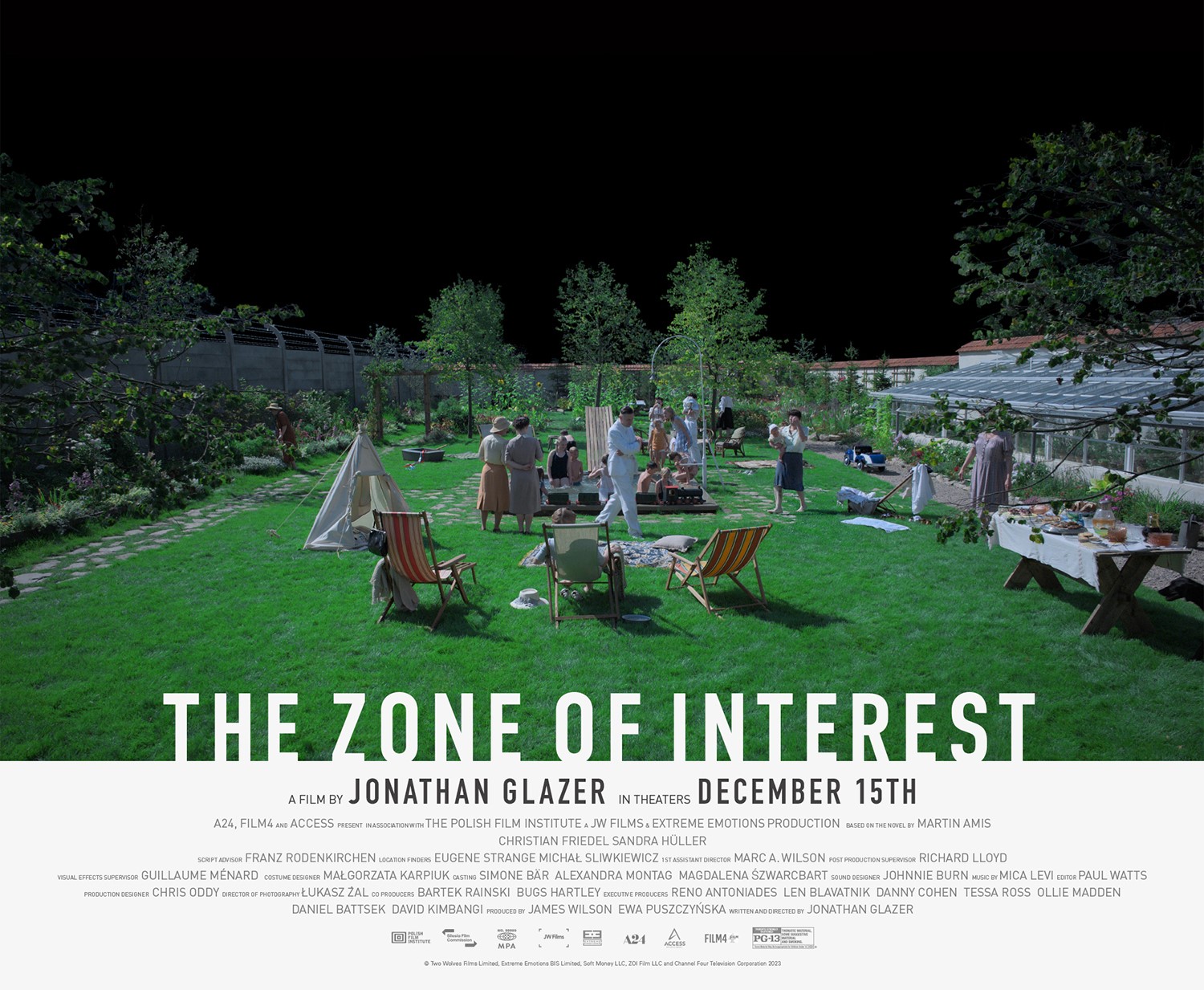

The movie, based on true events, follows Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss and his family as they build and maintain an idyllic lifestyle in their family home and garden. While we watch his wife Hedwig tend to her flowers and to her five Aryan children, the Holocaust’s deadliest camp sits just meters away from their garden wall, churning through hundreds of prisoners a day.

The film opens with a solid black screen that lasts for several seconds. As you stare into the void, the audio flows from strange distorted music, to the muffled sound of gunshots and screams, and finally to the garden’s singing of birds and other sounds of nature. Glazer has commented that this sequence is an invitation to listen, a reminder that what the audience hears will be just as important as what they see.

In this opening and throughout the film, Glazer has denied the audiences the visual horror they were probably expecting. He chooses instead to feature it only indirectly, usually in the form of sound: gunshots, guard dogs barking, officers screaming, fire and smoke spewing from chimneys, the hissing of gas. By leaving the violence almost exclusively offscreen, Glazer traps us in the Höss’s perspective — and by extension the perspective of German bystanders everywhere. Their willful ignorance was so powerful that it reduced genocide to background noise.

This approach establishes the dichotomy that is the fingerprint of Zone of Interest: watching a happy family go about their lives in the foreground while a massacre happens in the background. Spotless flower beds next to barbed wire — incompatible, incomprehensible, irreconcilable.

There are a few moments when Glazer lets us get a bit closer to the carnage, as if we might finally see the genocide with our own eyes, only to hold back at the last second. Rudolf takes his oldest son (a Hitler Youth member) on a horseback ride, where guards march a line of Nazi prisoners through the tall grass beside them, our view (and the son’s view) of them mostly obstructed. The younger son overhears his father outside ordering an officer to drown a Jewish prisoner in the river for fighting over food. His young daughter wanders the halls at night, gazing out the window into the fiery columns of smoke, seemingly haunted by what she does not fully understand.

The ways in which Rudolf veils the violence of his work from his family (and thus from us); the way that Hedwig builds a “paradise garden” next door to a death camp; the way that the lives of millions of innocent people are reduced to fodder for wively gossip; these are all ways in which real people throughout history have been able to ignore, promote, and actively assist in genocide. Keep conversations banal (blueprints of different furnace layouts to maximize efficiency). Talk in circles (discussions of reaching labor goals). Discuss plans for future vacations to Venice. Plant flowers. Eat lunch with neighbors.

Even without bloody violence, Zone of Interest is certainly disturbing. Hedwig’s visiting mother gazes up at the wall and muses that, “Maybe Esther is over there,” Esther being a Jewish woman whose house Hedwig’s mother used to clean. Or when Hedwig tells her mother, “Rudolf calls me the Queen of Auschwitz!” as they laugh together in the garden.

A prisoner drops off a sack of dresses and clothes, which the women rifle through. Hedwig tries on a fur coat and the lipstick she finds in its pocket and asks her husband to look for chocolate and treats for the children, if he can find them. They are shopping through items confiscated from prisoners, personal belongings of people who are now ash, the last lonely remnants of entire lives lived and stolen.

One of the neighbor's wives comments that one time among the spoils, she found some diamonds hidden in a tube of toothpaste. “They are very clever,” she remarks. Glazer seems intent on begging the question: Who is “they”? Are “they” the girls who clear the table, who Hedwig berates when she’s in a bad mood? Are “they” the man who slips into the house behind Rudolf to scrub his work boots clean? Are “they” us, the audience? Are “they” me, a Jew? Yes to all of the above.

The movie generates these internal dialogues in the viewers’ minds; in many scenes it felt impossible not to hear these questions in the back of my mind. Glazer is testing us. He asks, do you notice the green smoke above the fresh-cut grass? Do you hear the gunfire behind the gazebo? Do you know what is happening here? Are you sure?

Towards the end of the film, Zone of Interest becomes blatantly metatextual, which means it is self-referential; it comments on itself and breaks its own reality, which most movies try very hard not to do. It abruptly cuts to the modern-day Auschwitz museum being cleaned by custodians. We get glimpses of the exhibit windows which display endless piles of shoes, glasses, jewelry, and of walls with endless rows of faces and names.

Why break the illusion like this? Because this movie wants you to watch and to listen. Don’t look away while Rudolf sends memos, reads his children bedtime stories, and listens to football matches. Glazer is testing, too, whether he can trick us into forgetting what’s really happening. Maybe you’ll get bored of shallow conversations or watching the housekeepers clean the kitchen. But I’ve never seen a Holocaust movie where there’s a moment you ever forget you’re watching a Holocaust movie. It’s a delicate ploy, but it works here.

From modern day, cut back to 1943: Rudolf is leaving an office building in the wake of another promotion, and suddenly begins to retch. The hallway is empty and ominous. He looks around as if wary. I saw that and I wondered, Did he see behind the wall? Did he see what we saw? Did he see us?

Thumbnail image courtesy of A24